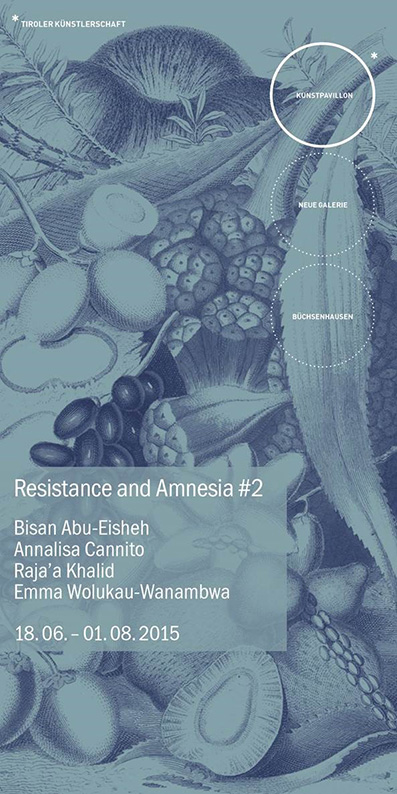

Resistance and Amnesia #2: On Failed Utopias, Living Myths and Coloniality Today

Bisan Abu-Eisheh, Annalisa Cannito, Raja’a Khalid, Emma Wolukau- Wanambwa, kuratiert von Andrei Siclodi

This exhibition was produced in the context of the International Fellowship Program for Art and Theory in Künstlerhaus Büchsenhausen 2014-15. Its participants were that year’s

grantees of the Fellowship Program, artists Bisan Abu-Eisheh, Annalisa Cannito, Raja’a Khalid and Emma Wolukau-Wanambwa.

Resistance and Amnesia #2 1 revealed moments of post-colonial amnesia in Europe’s public memory in an attempt to initiate a process to overcome them, thus reconstructing remembrance. Throughout this process, the aim was to question the (re-)gained knowledge with regard to its current relevance. The certainties generated by overcoming amnesia may unfold an emancipatory dynamic in the present day, which has the capacity to activate resistance against growing asymmetries between the global North and South – which go hand in hand with emerging inner social and economic asymmetries. So, what connects the political internment of a Palestinian communist by the Israeli regime in 1980; Mussolini’s call for donations of gold from the Italian population in order to finance the war against Ethiopia in 1935; the construction of the first luxury holiday resort in the Caribbean, in the former British colony of Jamaica, in 1953; the settlement of former Polish and Ukrainian prisoners of war by Lake Victoria, East Africa in 1941; and the opening of a mausoleum for a fascist war criminal in a small Italian village near Rome in 2012? All of these are manifestations of a process whose origins go back to the late 15th century, to the “discovery” of America: the global expansion of European modernity as a subalternizing system. These apparently disparate events taking place over a period of 80 years are all characterized by a colonial or post-colonial impetus to power – in short, by coloniality. This exhibition recounts coloniality’s forms, effects, and origins.

“It is useful to remember that the onset of modernity signified the – step-by-step, certainly, but nonetheless radical – transformation of the intersubjective structures that went before, as well as the formation of a unique model of rationality, which gradually gripped all the world’s population. One of the fundamental principles of this comprehensive change was a new understanding of time, according to which the past was replaced by the future as society’s principle horizon of expecta-tion […]”2 – as Venezuelan anthropologist Pablo Quintero writes. In the 20th century, this understanding of time applied to both the capitalist and the communist conception of world order. However, while the neoliberal, adaptive concept of capitalism (which which is now increasingly backing conservative protectionism in Europe) is surviving as a globally expanding ideology of real politics, despite all its supposed setbacks, and so celebrating an apparently unstoppable triumph, the communist utopia has been caught up in regional, real-socialist particularities and is ultimately failing as a political order.

But the work of artist Bisan Abu-Eisheh, who comes from Palestine, reminded us at the beginning of the exhibition that there is more than just one, dualistic way of viewing things here: that the capitalist form of rule can generate different types of coloniality (sometimes based on religion), making an ethnic group, itself suppressed and persecuted for centuries, into a persecutor. A live music set was erected, with an acoustic guitar, a drum, a tambourine, two microphones, a stand for the score – all waiting for the players. Meanwhile, a song could be heard through an old loudspeaker. The melody in the style of Bob Dylan sounded familiar, the song is about being imprisoned, about longing and love. Later in the song, however, it became clear that it also deals with a free Palestine; it is about the long struggle to get there, battles for liberation, and the class struggle. Indeed, in a long-term artistic investigation Bisan Abu-Eisheh examines questions of identity on the basis of a private archive belonging to his father, who was denounced as a member of the Communist Party of Palestine in 1980 and consequently was interned in an Israeli political prison for three years. Among the reminders of this period are letters to his wife, the artist’s future mother, but also photos of friends and acquaintances that the artist’s father received in prison. For the installation in the Kunstpavillon Bisan Abu-Eisheh translated his father’s letters into German. Musician Kamil Szlachta was commissioned to write lyrics that retain the essential stylistic features of the letters from this text (the pathos, the rhetoric), and so to compose and perform a song. In this context it was, not least, a case of expressing the myth of the communist promise – of its lasting vitality despite obvious failure – but also of revealing the pathetic address that is characteristic of the Arabic language. The physical absence of the singing voice creates a nostalgic effect, a melancholy longing for the utopia of a better life, which is even further away now than before.

The “scientific” exploitation of nature – in particular of useful plants from a foreign, “far-flung place”, the former German colonies – was one of the central themes in the installation Idyllic Place or State by Raja’a Khalid. Herein she focused our – primarily olfactory – attention on the collection of useful tropical plants in today’s Botanical Gardens in Berlin. This collection originated with the Central Botanical Office for the German Colonies, founded in 1891, the aim of which was to organize the testing and dissemination of commercially exploitable plants from and in the German colonies. Many of these plants were “discovered” and exploited commercially during the course of violent conflicts. For this reason, Raja’a Khalid views the “Greenhouse C – Useful Plants” in Berlin’s Botanical Gardens as a “colonial gesamtkunstwerk of botanical materials and their gathering”. The artist took a sample of the highly scented air in this greenhouse and sent it to a laboratory for analysis of its aromatic combination. A professional perfume-developer then produced a scent that came as close as possible to the original air (at least insofar as the artist’s memory can be relied upon). An industrial aroma diffuser enabled visitors to experience this perfume in the exhibition. In close proximity to this earthy perfume one could see the framed photograph of a stereotypical “blond female beauty” on a sandy beach. An indication of where the photo might have been taken is provided by the hibiscus plants also to be found in the room: originating in Jamaica, these are available world-wide today, both as a type of tea and as a decorative pot plant. The woman depicted is Liz Benn, one of the most famous models of the 1950s, who is posing here for “Vogue” magazine “somewhere” on a Caribbean beach. Here, according to Raja’a Khalid, colonial botany hands over the baton, so to speak, as far as the creation of exotic images of longing is concerned, to the post-war fashion and tourism industry. Liz Benn married John Pringle, an entrepreneur who received 100,000 acres of sugar plantation beside Montego Bay in Jamaica from his Scottish grandfather; from 1953 he had this area redesigned to create the world-famous luxury resort for rich Americans, Round Hill. At that time Round Hill was a pioneering achievement of its kind, copied all over the world in the following decades. Today, many such resorts are to be found in former European colonies in the Caribbean, on the east coast of Africa, in East Asia and the South Pacific.

The promise of a better, even paradisal life also plays a cen-tral role in the work Promised Lands by Emma Wolukau- Wanambwa. A bright-orange painted cabin constructed especially for the purpose harbored a single-channel video, in which the image was accompanied by a narrative voice. This video essay shows the uncut, static recording of a rural landscape during sunset. Taken at an unspecified location in eastern Uganda with the auto-focus setting permanently “on”, the darker it becomes, the more frenziedly the camera attempts to sharpen the image. The voice of the artist, who speaks through the twilight, reflects on definitory power with regard to the drawing of borders. “Words kill”, she states, and offers in the subsequent images textual explanations – like dictionary definitions – of the concepts “fiction”, “art” and “artificial”. It is about observation as such, about the importance of acuity, the sharpening of perception. While night falls gradually, Emma Wolukau-Wanambwa takes us on a meditative journey making use of a range of sources: excerpts from the novel Freiland. Ein soziales Zukunftsbild (Freeland: A Social Anticipation) (1890) by Theodor Hertzka; the artist’s encounter with people who worked in the isolated European refugee settlement beside Lake Victoria between 1941 and 1953; and impressions at the end of a night train journey from the Brenner Pass to Innsbruck. Promised Lands by Emma Wolukau-Wanambwa makes it clear that utopias in the European-western sense have always been a colonial project, and that their realization in a region necessarily conceived as empty, but de facto never truly so, inevitably went hand in hand with the ruthless displacement and subalternization of those people who had lived there before. She also, however, reminds us that this process not only represents something historical, belonging to the past, but also uncovers a direct impact on our present.

In the darkened, black-painted room right at the back of the exhibition space, Annalisa Cannito led us to another link with an historical trauma not yet resolved and highly relevant to the present day – into the “belly of fascism and colonialism”. She showed four works that combined an object and a montage of TV news, confronting these with original historical material, overlapping photographic and cinematographic images in a multiple projection. At the visual center of the multimedia installation we found Life Saver, a gilded life-preserver made from concrete, which hung in the center of the facing wall. The sculpture highlighted two references, one historical and one to the present day. The historical significance was made clear by an original postcard dating from the year 1935, mounted alongside the sculpture, that was bearing a slogan of Mussolini’s fascist regime: “L’oro alla patria” (gold for the fatherland), was proclaimed after the League of Nations (the predecessor organization to the UNO) had imposed economic sanctions on Italy because of its open aggression towards Ethiopia. With respect to the present, the heavy stone life-preserver pointed to the problems of European migration policy. Contesting Europe Corporate Hypocrisy #2 is a video collage of TV news, which the artist gathered on the Internet. It made clear how (often unintentional) racist patterns of behavior and oppression in political speeches and acts are spread with the aid of the mass media, and motivated behavior to oppose this tendency. The original document belonging to this work – a notebook from the fascist era – illustrates a situation that could date from the present time: on the back of the cover we read “Mare Nostrum” (also the title of an operation by the Italian coast guard service in 2013-14), while a dramatic sea battle is depicted on the front. Finally, Intervention in Spaces of Amnesia #2 questioned forms in which the memory of fascist colonial criminals are idolized in today’s Italy. In August 2012, in the small village of Affile near Rome, a mausoleum was built in honor of its former citizen Rodolfo Graziani, a fascist war criminal responsible for atrocities against the anti-colonial resistance in Libya and Ethiopia. Annalisa Cannito overlayed a photographic image of the mausoleum with the projection of a film that was censored for almost thirty years in Italy: on the basis of accurate historical research, The Lion of the Desert by Syrian-American director Mustafa al-’Aqqad visualizes not only the violence and crimes of the Italian army in Libya under Graziani’s leadership from 1929–1931 but also the anti-colonial resistance, which was led for several decades by resistance fighter Omar el- Muktar. Screening of the film in Italy was banned in 1982, one year after its release: Giulio Andreotti, the Prime Minister at the time, justified this ban by arguing that the film constituted an insult to the Italian army.

——

1 The exhibition in the Kunstpavillon was a continuation of the exhibition already shown at Künstlerhaus Büchsenhausen in autumn/winter 2014 Resistance and Amnesia #1 – On the

Formation of Social Memory.

2 Pablo Quintero: Entwicklung und Kolonialität, in: Pablo Quintero and Sebastian Garbe (eds.): Kolonialität der Macht. De/Koloniale Konflikte: Zwischen Theorie und Praxis, Münster

2013, pp. 93-114, quoted here from p. 95.

Opening: June 17, 2015 at 7 p.m.

Welcoming: Christoph Hinterhuber, Member of the board, Tiroler Künstlerschaft

Introduction: Andrei Siclodi, Curator