To a certain degree sacredness is in the eye of the beholder – Act V

Stefania Strouza

Stefania Strouza’s artistic practice has evolved between Vienna and Athens in recent years. Her works are concerned with political spaces and aesthetic practices; with their immanent ambiguities and the conflicts addressed within them. Utilizing a range of media, the artist attempts to connect objects and spaces with existing social and cultural narratives, examining their potential step-by-step abstraction and transforming them into a dialogical state. She works with sculptural and structural aspects, architectonic constructions and dramatic staging.

Strouza’s oeuvre evidences her openness to different disciplines, oscillating between western and eastern-influenced ideas and visual languages. In her most recent works she investigates the relationship between modernist vocabulary and its fragmented historical and subjective substantiation.

In her solo exhibition at Neue Galerie the artist showed the spatial installation To a certain degree sacredness is in the eye of the beholder – Act V. To a certain degree… is a work in progress, articulated in a number of versions or acts. Its starting point lies in two journeys: one made to Athens by important representatives of modernism for the Congrès Internationaux d’Architecture Moderne (CIAM) in 1933, and one made by Euripides’ Medea in the 1969 film by Pier Paolo Pasolini with Maria Callas in the leading role. The series of international congresses for Neues Bauen (from 1928 to 1959) defined discussions of urban planning and the development of modern architecture.1 The ship Patris II sailed from Marseilles in 1933, bringing both established leaders of the avant-garde – such as Le Corbusier, László Moholy-Nagy, Otto Neurath and Fernand Léger – and young, up-and-coming architects to Athens in order to discuss the “functional city” during the voyage. This journey through the Aegean also marked a shift in the geographical focus of the CIAM and changed its key themes. Subsequently there was a turning away from the centre of Europe towards the Mediterranean, to the vernacular buildings of Greek villages with their white cubes, and to the original architectonic ideals expressed in the temples of antiquity. For all those who could not be there, the white ship also conjured the image of an ark, on which the ideas of modernism could weather the harsh storms of the war years.2 The congress exercised an influence on Greek artists of the period and simultaneously raised questions about what constituted Greek modernism.

36 years later, Italian director Pier Paolo Pasolini staged a journey in film: a free interpretation of an ancient Greek myth, based on the literary model by Euripides dating from 431 BC. Pasolini’s film uses motifs from the myth of Medea and the saga of the Argonauts to show an encounter between two cultures. The incompatible nature of these cultures causes the relationship of the two leading characters – the pragmatic, rationalist Greek Jason and the archaic, animist priestess Medea – to end in a bloody tragedy.3

In the project To a certain degree sacredness is in the eye of the beholder, Strouza sets these two journeys, one historical and one cinematic, one from West to East and the other from East to West, into a broader debate on Greek modernism. Using this narrative as “construction material”, the artist creates a number of sculptural presentations. The works are connected and permit a range of associations: from modernist design and primitive culture to a group of hybrid constructions that fluctuate between functionalism, decoration and abstraction, and ultimately to geographical locations. These fragile aspects function as quiet pointers, symbolically examining the encounter between East and West, where the tradition of the visual language of antiquity confronts a modern European understanding of the world.

In the Neue Galerie Stefania Strouza staged Act V of To a certain degree. In Act V the individual works achieved a mediating character as latent presences, silent mentors, apparently pointing to a fundamental cultural dispute. The artist utilized the affinity of architecture, sculpture and textiles as a kind of stage setting. In the window to the corridor, the artist placed a sculpture which could be viewed from the outside, as if in a “Guckkasten”(kaleidoscope). In the first scene of Act V the concrete objecton this miniature stage became an architectonic form in itself, reminiscent of an architectural model or part of a Greek column. Similar concrete sculptures could be found in varying forms in the separate, staged spaces of the exhibition. They refer to forms that support or are supported themselves; however, in some cases they appear as if in a state of incompleteness.

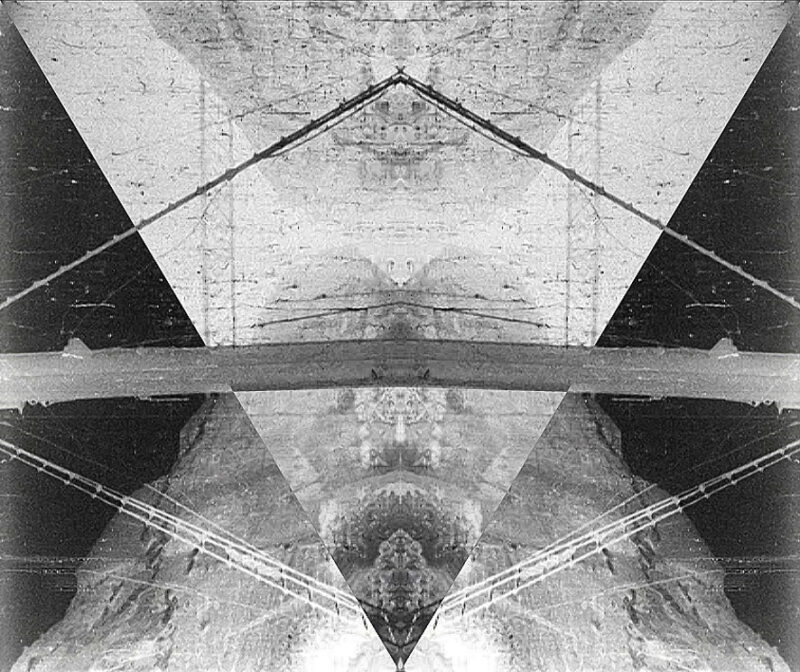

In the entrance area, before entering further scenes, the visitor found a row of “photographs”, presented in this form for the first time in an exhibition context. They could be understood as an introduction to the artist’s work but also as a preface to the 5th act. For an earlier work entitled Black Athena, Strouza produced clay imprints of a miniature statue of the Greek goddess Athena, which here she now scanned and printed onto photo paper. This series of three “photographs” hung between a row of collages made using stills from a documentary film of the CIAM trip to Athens by László Moholy-Nagy.4 Screenshots are used as positive and negative images, mirrored, and also printed onto photo paper. The artist selected three shots from the film in which the ship is passing through the Corinth Canal. This moment of the voyage was selected by Strouza, as symbolizing the transition from West to East. The reduction of the images to sculptures and sculptural abstractions lead on directly to the scenes in the other gallery rooms. The collages of the documentary film are reminiscent of the structure of skeletons, echoed in the metallic sculptural elements, and the surfaces of the photographs of Athena remind us of the haptic quality of skin, thus referring to the textile materials used.

A series of sculptural stagings, either free-standing in the space or hanging on the wall, made direct reference to the architecture of the gallery rooms. These objects were made of steel, playfully handled and combined in various ways using textile materials. The artist used Le Corbusier’s Le Modulor scheme of proportions as her starting point for the dimen-sions of the metal objects, cutting the original scale from one oriented on a human 1.83 meters tall to fit the measurements of her own body, and set it in relation to the space as found and the surrounding walls of the gallery area. Vitruvius drew attention to the model of the human figure for the architecture of temples,5 and Le Corbusier’s Modulor may be regarded as the most significant modern attempt to lend mathematical order to architecture oriented on human dimensions.6

In her past works the artist has often experimented with a variety of different textiles, and for this exhibition she used artificial, bronze-colored leather. This material has similar structural and haptic qualities to human skin, and referred also to antiquity (e.g. the Golden Fleece). Strouza printed a pattern suggestive of mythological models and derived from the original lettering of “Medea” from the Pasolini On the one hand, the textiles were used as a kind of curtain for a stage-like setting. On the other, they recalled sewing patterns for robes that could be used for solemn occasions, ceremonies or performances. Did Maria Callas wear one of these robes for the Medea film, for example? Or the artist, during a performance that has happened already or is due to take place? In the last room the stage closed to create a space within a space, as the final scene in Act V of To a certain degree sacredness is in the eye of the beholder.

In Act V Stefania Strouza invited visitors to a journey between East and West, and to an investigation into modernism on both sides of the Corinth Canal.

Text: Cornelia Reinisch-Hofmann

——

1 Cf. Daniel Weiss, Bestandesbeschrieb CIAM, in: Website des gta Archivs / ETH Zürich, Dezember 2009, www.archiv.gta.arch.ethz.ch/sammlungen/ ciam/informationen. (09.06.2015)

2 Cf. Gregor Harbusch, Kreuzfahrt der Moderne, Baunetzwoche#395, 29.01.2015 (www.baunetz.de, 09.06.2015), pp. 8-18.

3 Cf. http://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Medea_%281969%29 (09.06.2015)

4 Video: www.ciam4.com/video-en/ciam-4-filmed-by-laszlo-moholy-nagy/, May, 2015

5 Cf. Paul von Naredi-Rainer, Architektur und Harmonie. Zahl, Maß und Proportion in der Abendländischen Baukunst, Cologne, 1999, p. 84.

6 Cf. Paul von Naredi-Rainer, Architektur und Harmonie, Cologne, 1999, p. 101.

Opening: June 10, 2015 at 7pm

Welcoming: Carmen Brucic, Member of the board, Tiroler Künstlerschaft

Introduction: Cornelia Reinisch-Hofmann